| Endocrine Disruption |

The Hormones : Androgens Most animals depend on the versatile estrogens to influence growth, development, and behavior; regulate reproductive cycles; and affect many other body systems. The hormones, though, are more plentiful and play a larger role in females than in males. In women, estrogen levels vary through life, surging at adolescence, seesawing monthly in the reproductive years, and waning to low levels during menopause. Although indispensable, too much estrogen exposure is linked to some cancers. This little understood paradox between health and disease continues to spur public attention and scientific interest.

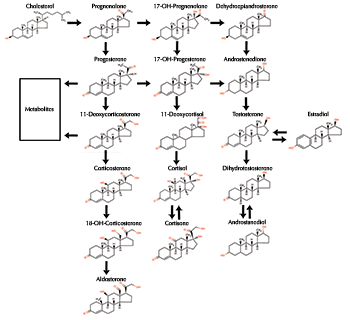

CAPTION: Testosterone is a potent androgen. (click image to manipulate). CREDIT: PubChem, National Library of Medicine. Construction and Production  Androgens are a group of chemically related sex steroid hormones. Steroids are a special kind of fat molecule with a four-ringed, carbon atom backbone or core, like their cholesterol predecessor. Androgens are a group of chemically related sex steroid hormones. Steroids are a special kind of fat molecule with a four-ringed, carbon atom backbone or core, like their cholesterol predecessor. CAPTION: A series of chemical changes turns cholesterol into androgen hormones. CREDIT: Tulane University. A series of chemical reactions spurred by proteins called enzymes remove and add groups to cholesterol's polycyclic (many-ringed) core. These actions transform cholesterol first into the steroid pregnenolone, then into testosterone and other androgens. In humans and other vertebrates, androgens are made primarily in the male testes, female ovaries, and adrenal glands. Kinds and potencies vary among animal groups. Testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (17-beta-hydroxy-5-alpha-androstan-3-one) are the most potent androgens in humans and four-legged vertebrates. The weaker androgens androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) occur in small amounts in all vertebrates. Although 11-ketotestosterone is a weak androgen in four-legged vertebrates, it is the most potent variety in bony fishes and sharks. back to top Revving Up

Like all steroid hormones, androgens produce effects by docking with receptors on the cell's membrane surface or inside the cell in the liquid cytoplasm. Receptor binding triggers different chemical signaling systems depending on receptor location. A steroid hormone uniting with a surface receptor starts a lightening-fast chemical relay in the cytoplasm that changes cell chemistry and initiates hormone release, blocks cell death, or nudges the cell from the resting to growth phase of its life cycle. In contrast, when steroid hormones go inside a cell, they can unite with a receptor to form a hormone/receptor unit that moves into the nucleus, attaches directly to special DNA binding sites, and activates protein-producing genes. The proteins drive the cell changes guiding androgen-controlled growth and development (Cato et al. 2002). back to top Effects Androgens control male sex traits and development and influence female sexual behavior. Hormones and genetics together guide gender and sexual features in the developing vertebrate embryo. In humans, the Y chromosome first determines the sex as male. Other animals also have sex chromosomes, but in some fish and reptiles, the physical environment, especially temperature of the embryo, is more important for determining male sex. After male sex is determined, androgens orchestrate growth and development of the male reproductive system, including the penis, testes, prostate, sperm, and other essential features. Later in life, the hormones trigger male puberty, influencing vocals (bird songs, amphibian calls, human's deep voice), body ornamentation (human facial hair, bird feather color, fish skin color), muscle mass, and behaviors such as sex drive and aggressiveness. Androgens also influence female sex drive. back to top Androgen Disrupters Some compounds in the environment can chemically neuter animals by blocking androgens' effects. These antiandrogens block production of androgen hormones or clog receptors, keeping true androgens out. A group of industrial chemicals known as phthalates can reduce testosterone production in fetal testes causing sex-organ defects and loss of reproductive functions in animals (Gray et al. 1999; Thompson et al. 2004). Limited research suggests these chemicals, found in personal care products and most soft plastics, may affect human genital development in similar ways. Phthalates are associated with several subtle, yet potentially serious, genital changes in baby boys whose mothers, when pregnant, had elevated levels of the chemicals in their urine. The boys' shortened anus to penis distance, incomplete testes descent, and smaller scrotum and penis may forewarn of infertility or cancer later in life (Swan et al. 2005). Animal studies confirm the fungicides vinclozolin and procymidone, the herbicide linuron, and the DDT-insecticide breakdown product p,p'-DDE block androgen receptors and hinder development and function of the penis, testes, epididymis, and other masculine structures in male offspring (Gray et al. 2001). Research History Scientists have studied androgens since the 18th century. John Hunter initially described androgenic actions in 1771. He transplanted a rooster’s testes into a hen and found she grew rooster-like combs and wattles. In 1849, A.A. Berthold transplanted testes from a normal rooster into a castrated rooster. The castrated rooster regained his combs and wattles, his crowing voice, and his fighting behavior (Hadley 2000). Almost a century later, in 1935, Leopold Ruzicka worked out the chemical structure of the "androgenic principle" from the testes, calling it testosterone (Hadley 2000). back to top References

back to top |