Endocrine Disruption

|

Phytoestrogens

CAPTION: Many fruits and vegetables contain phytoestrogens.

CREDIT: Wikimedia Food and Drink

We are exposed daily to highly variable amounts of phytoestrogens. While adults eating a vegetarian diet or those taking dietary supplements containing phytoestrogens have high levels of exposure, infants drinking soy-based formula have the highest exposure levels by far. In most cases, the soy formula is the only source of nutrition for these infants during their first few months of life. The infants, then, are exposed to 10 times greater concentrations of phytoestrogens than adult vegetarians. CAPTION: Plant compounds, such as the isoflavones found in soybeans and other legumes, can have health benefits and risks. CREDIT: Wikimedia According to recent estimates in the United States, more than 15 percent of babies are given soy formula. In the United States, soy formula is easily available “over-the-counter.” However, in European countries, it is available by prescription only. The isoflavones genistein and daidzein are two phytoestrogens found at very high levels in soy formula. There are currently differing opinions about the role of phytoestrogens in health. For adults, when consumed as part of an ordinary diet, phytoestrogens are considered safe and possibly beneficial. Some studies on cancer incidences in different countries suggest that phytoestrogens may help protect against certain cancers (breast, uterus, and prostate). However, it is still unclear whether this beneficial effect is due to increased amounts of phytoestrogens in the diet or to the resulting low fat content of the diet. Similar beneficial effects of dietary phytoestrogen supplements have not been documented. On the contrary, eating very high levels of phytoestrogens may pose health risks. Studies with laboratory and farm animals, as well as wildlife eating high amounts of phytoestrogen-rich plants, have documented reproductive problems. back to topPossible Health Benefits

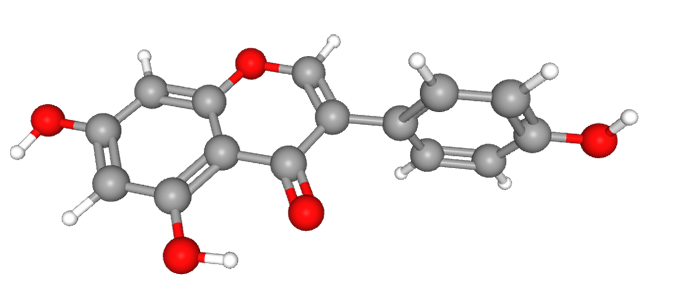

CAPTION: Soybeans and other legumes contain the estrogen-like genistein. (click image for PubChem Compound Summary). CREDIT: PubChem, National Library of Medicine Laboratory animal studies and comparisons of Asian and Western human populations suggest that diet plays a large role in these types of health problems. Asian populations generally eat large quantities of soy products compared to Western populations. One study found that Asian populations have lower rates of hormone-dependent cancers (breast, endometrial) and lower incidences of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis than Westerners. Asian immigrants living in Western nations also have increased risk of these maladies as they “Westernize” their diets to include more protein and fat and reduce their fiber and soy intake (Kao and P'Eng F 1995). Other studies also suggest that phytoestrogens may offer long-term protection against some cancers including breast, colon, prostate, liver, and leukemia. According to some animal studies, phytoestrogens (mostly those found in soy-based products) eaten as part of an adult diet can protect against some types of cancer and may even inhibit tumor growth. Another animal study found that young rats injected with genistein (a soy isoflavone) and then exposed to a cancer-causing agent later in life developed fewer mammary tumors and waited longer to develop them than the non-exposed rats (Lamartiniere et al.1998). Another study reported that infants on soy based infant formulas have improved cholesterol synthesis rates later in life (Setchell et al. 1997). This study supports the idea that phytoestrogens are bioactive and can have an effect in humans even at levels found in soy infant formulas. Gaining these possible benefits may involve more than just eating more soy products. Asians, for instance, have been eating these compounds for thousands of years and may have evolutionary adaptations that allow them to use phytoestrogens to their advantage. And, some plant and soy products contain other potential anti-cancer substances (such as protease inhibitors and antioxidants) that may be responsible for the proposed health benefits (Makela et al. 1995). Evaluating health effects of phytoestrogens is difficult and depends on numerous factors, including the kind and dose (amount) of phytoestrogens eaten and the age, gender, and health of the person. For instance, the very foods that interfere with the endocrine messaging centers during a baby's development may help protect against breast and prostate cancer in adults. Why? There is strong evidence that lifetime exposure to natural estrogens, such as estradiol, increases the risk of certain kinds of cancer, such as uterine cancer. Phytoestrogens may help reduce that risk because they may lower a person's lifetime exposure to natural estrogens by competing for estrogen receptor sites or changing the way natural estrogens are broken down. It is possible that these endocrine interferences can reduce a person's exposure to natural estrogens thus reducing the cancer risk in so called target tissues, mostly reproductive organs that respond to sex hormone signals. back to topPossible Health Risks As for adverse health effects, the most likely risks associated with phytoestrogens deal with infertility and developmental problems. Humans have used plants for medicinal and contraceptive purposes for eons. According to modern-day analyses, many of the plants historically noted for their ability to prevent pregnancies or cause miscarriages contain phytoestrogens and other hormonally-active substances. For instance, during fourth century BC, Hippocrates noted that the wild carrot (now known as Queen Anne's lace) prevented pregnancies (Riddle 1991). Its seeds, we now know, contain a chemical that blocks progesterone, a hormone that is necessary for establishing and maintaining pregnancy.

CAPTION: Animals eating phytoestrogen-rich diets, such as sheep grazing exclusively on clover, can experience infertility and reproductive problems. CREDIT: Needpix Australian sheep suffered from reproductive problems and infertility after grazing in pastures with the phytoestrogen-containing clover Trifolium subterraneum (Bennetts and Underwood 1951). Two phytoestrogens, equol and coumestrol, were identified as the culprits. A group of captive cheetahs experienced infertility while on a diet rich in soy (Setchell et al. 1987). When the soy was replaced with corn, their fertility was restored.Additionally, phytoestrogens may influence development and trigger life-long effects. Mice and rats exposed before or right after birth to several phytoestrogens, including coumestrol and genistein, develop adverse reproductive function later in life. The studies report altered ovarian development, altered estrous cycles, problems with ovulation, and subfertility (fewer pregnancies; fewer pups per litter), and infertility (Delclos et al. 2001; Jefferson et al. 2002b, 2005, 2006; Kouki et al. 2003; Nagao et al. 2001; Nikaido et al. 2004; Whitten et al. 1993). Other rat studies find developmental exposure to genistein alters pituitary responses that contribute to the ovulation problems (Faber and Hughes 1993; Levy et al. 1995). Altered mammary gland differentiation leading to increased cancer risk is also reported following developmental exposure to genistein (Hilakivi-Clarke et al. 1999). In addition, mice treated right after birth with genistein had an increased incidence of uterine cancer later in life (Newbold et al. 2001).

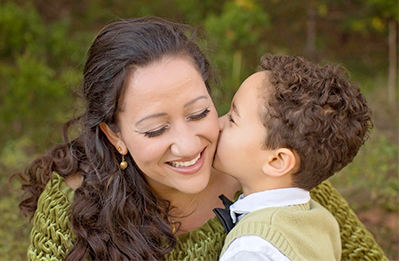

CAPTION: Developing fetuses and infants may be at the most risk from exposure to high levels of hormone-like plant compounds. CREDIT: Pixnio Other studies show young adult men and women fed soy based formulas as infants had increased use of allergy medicines and women had longer menstrual bleeding and more discomfort during the menstrual cycle than their counterparts who were fed cow based formula (Goldman et al. 2001; Strom et al. 2001). This is remarkable considering the small sample size in that study (268 women in the cow based formula group and 128 in the soy based formula group). Therefore, the adverse effects of developmental exposure to genistein remain of particular concern. Phytoestrogens behave like hormones, although they are generally less potent. Like any hormone, too much or too little can alter hormone-dependent tissue functions. Taking too much of any hormone may not be good for humans or animals. Similarly, too many phytoestrogens, at the wrong time, may lead to adverse health effects. Experimental animal studies, such as those outlined, can help us define dietary levels that are safe and clarify the possible reproductive and developmental risks associated with phytoestrogens. back to topAn Explanation Some scientists believe that plants make phytoestrogens as a defense mechanism to stop or limit predation by plant-eating animals (Ehrlich and Raven 1964; Guillette et al. 1995; Hughes 1988). Instead of protecting themselves with thistles or thorns or tasting bad, these plants use chemicals that affect the predatory animal's fertility. Although using estrogen-mimicking compounds for protection may sound far-fetched, it makes sense from an evolutionary stance. Many real-life examples support the theory that plants and animals change together, or co-evolve, over time. The explanation goes something like this: to avoid predation, plants produce compounds (phytoestrogens) that limit an herbivores reproduction. Thus, the predator's population decreases and more plants can prosper. But remember, because of genetic differences, not all species or individuals of a given species will react to the phytoestrogens in the same way. While some herbivores may show fertility problems, others may acquire resistance - like some insects are resistant to pesticides and some bacteria can survive antibiotics. Likewise, some humans may be more susceptible to the benefits and risks of phytoestrogens than others would be. back to topFurther Resources About Herbs, Botanicals and Other Products Web site. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

back to top |

Diets rich in certain phytoestrogens also adversely affect the fertility of experimental and domestic animals. For instance, phytoestrogens in dry, summertime grasses reduced the number of offspring in wild populations of California quail (Leopold et al. 1976) and deer mice (Berger et al. 1977).

Diets rich in certain phytoestrogens also adversely affect the fertility of experimental and domestic animals. For instance, phytoestrogens in dry, summertime grasses reduced the number of offspring in wild populations of California quail (Leopold et al. 1976) and deer mice (Berger et al. 1977).

Some researchers are most concerned about exposure of unborn fetuses and infants to high levels of phytoestrogens since development is highly controlled by hormones of the endocrine system. Human epidemiology studies document adverse effects of genistein. One study found that women eating a vegetarian diet during pregnancy have male offspring with an increased incidence of hypospadias, possibly due to high maternal levels of soy isoflavones (North and Golding 2000).

Some researchers are most concerned about exposure of unborn fetuses and infants to high levels of phytoestrogens since development is highly controlled by hormones of the endocrine system. Human epidemiology studies document adverse effects of genistein. One study found that women eating a vegetarian diet during pregnancy have male offspring with an increased incidence of hypospadias, possibly due to high maternal levels of soy isoflavones (North and Golding 2000).